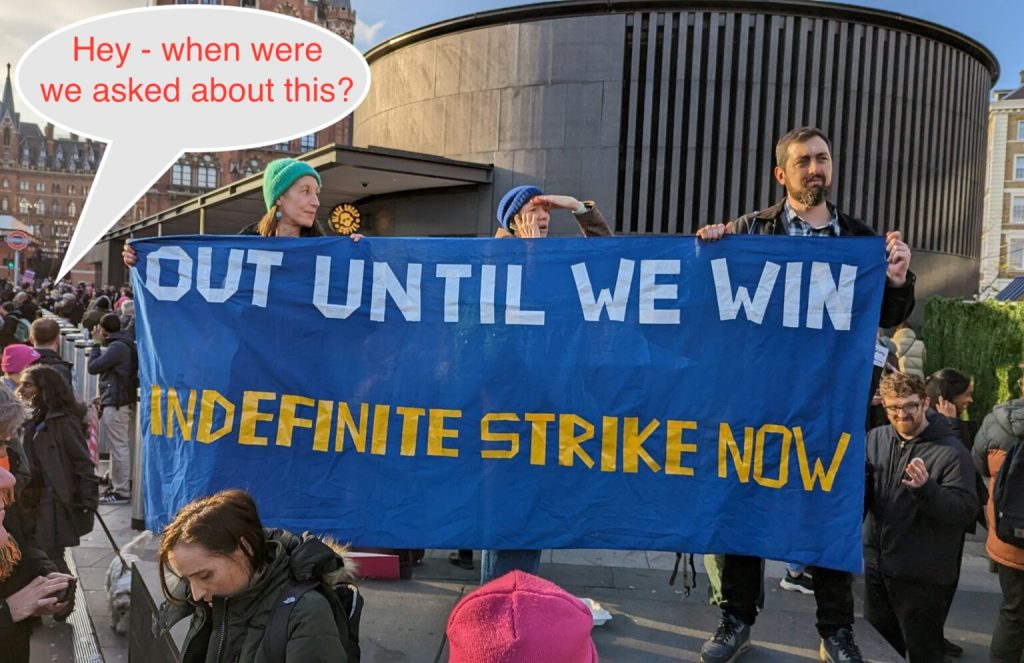

At the UCU Higher Education Committee (HEC) meeting on 12 January, members of the UCU Left faction voted for an indefinite strike starting 1 February. Only two days previously a meeting of UCU branch delegates (BDM) voted almost 2:1 to reject this proposal, with less than one third favouring an indefinite strike. Thanks to UCU Left it is now union policy that the views of a BDM should give a ‘strong steer’ to the next meeting of HEC, yet the UCU Left faction deliberately flouted this prescription and ignored the majority view. Why did those who claim to advocate a ‘democratic’ and ‘member-led’ union so egregiously ignore the views of the majority of union members, as reported at the BDM? And how do their actions relate to the policies and objectives of the UCU Left candidates who are standing in the current elections to the UCU National Executive Committee?

Socialist Workers Party influence in UCU Left

To answer those questions, we have to dig a little deeper into the origins and objectives of UCU Left. With its own website, regular posts, occasional meetings, AGMs (the most recent on October 6), lists of candidates for union office and an annual membership fee of up to £30, UCU Left is an exceptionally well-organized trade union faction.[1] Less well-known, and absent from its website, is the fact that it was initiated and has always been controlled by the Socialist Workers Party (SWP)[2], a small Trotskyist organization dedicated to the revolutionary overthrow of capitalism and the suppression of parliamentary democracy.[3]

Whilst many UCU Left candidates are not members of the SWP, and may not even support that organization, the core leadership of UCU Left comprises long-standing members of the SWP who control and direct factional policy in line with, and under the guidance of, senior members of their party.

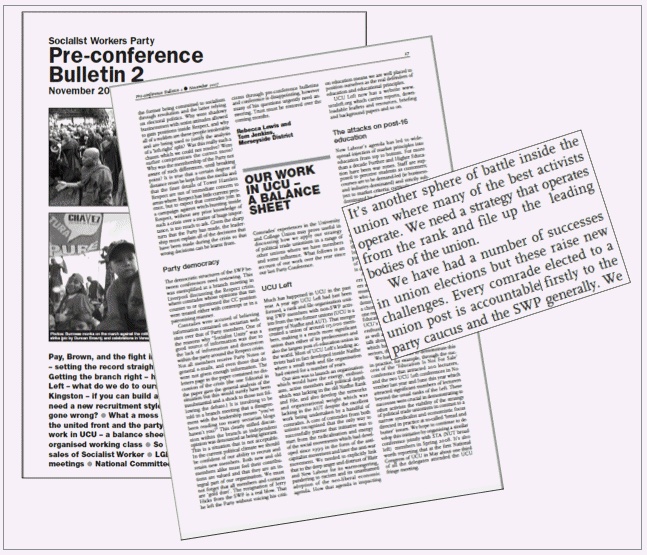

This is nothing new – the SWP internal bulletin discussed their strategy as long ago as 2007 (see p27 for ‘Our work in UCU – a balance sheet’). In the same bulletin a statement from the SWP Central Committee stated “Every comrade elected to a union post is accountable first to the party caucus and the SWP generally. ….we cannot allow bureaucratic pressure to blunt our politics”

For the SWP, trade unions are ‘schools of war’ and strike action is the principal mechanism through which ‘non-revolutionary workers begin to change their thinking.’ The SWP describes itself as ‘a party of leaders’, the vanguard of the working class, whose role is to give ‘direction to the struggles around them’ in order to help fuse ‘militant workplace action and revolutionary politics’ and ‘recruit people to revolutionary organization [the SWP]’.[4] Trade union action alone is inadequate for workers because it does not set out ‘to destroy the [capitalist] system.’[5] In contrast, the reason most university employees join a union is for ‘protection at work in case of a problem’. Their purpose in undertaking collective action is to secure an improvement in terms and conditions of employment through a negotiated agreement with the employers. SWP activists are far less interested in these issues and wary of negotiated agreements that end disputes; they are far more concerned to press for total victory and typically dismiss anything less as a ‘sell out’ by the ‘union bureaucracy’. Above all they seek to promote strikes as the means for developing class consciousness and building the revolutionary party, the sine qua non for the revolutionary seizure of power.[7]

Effect on UCU industrial action strategy

Within UCU, it had become clear by 2017 that the pattern of short one-day strikes, pursued through successive bargaining rounds 2019-20 and 2021-22, was having very little impact. A Commission on Effective Industrial Action was established the same year, but successful mobilization by UCU Left resulted in its numerical domination of that newly-created body. What the Commission should have done was examine the various forms of leverage open to the union, such as assessment boycotts and disruption of university events and income streams, and the causes of UCU weakness, such as low union density: less than 40 per cent of university employees are members of a trade union. Despite some valuable recommendations on dispute planning, its main thrust was to frame the debate about collective action as a choice between short strikes and marking boycotts (ineffective) versus ‘sustained strike action’ (effective).

The first fruits of this policy emerged in 2018 in response to the employers’ plan to destroy the USS defined benefit pension scheme and replace it with an inferior defined contribution scheme. 14 days of strike action persuaded employers to retain defined benefit pensions and secured the establishment of an independent, Joint Expert Panel to examine and report on the protection and improvement of the existing pension scheme. When the General Secretary declared these outcomes to be a win, UCU Left was repelled by anything less than total victory and horrified at the prospect of a cessation of strike action. Its online posts declared that a ‘growing number’ of branch meetings had rejected the ‘sell out’ settlement. Average attendance at these meetings was just 8 per cent and their unrepresentativeness became clear when a ballot of all UCU members accepted the union recommendation by a clear 2:1 majority on a substantial 64 per cent turnout.

Effect on UCU democracy

What also became clear in the pensions dispute is that when UCU Left talks about a ‘member-led’ union, what it actually means is an organization led by the small minority (perhaps around five per cent) who regularly attend branch meetings. These are typically the more active and more militant members whose views are more likely to coincide with the policies of UCU Left, in contrast to the ‘median’ union member, many of whom, in the dismissive words of SWP founder Tony Cliff, were ‘uninformed and conservative’.[8] The bias towards an activist minority helps explain why UCU Left is content with poorly attended meetings and deeply hostile to the idea of membership surveys or referenda. The UCU Left candidates’ manifesto for the 2023 NEC elections includes the following, which shows their attitude to participation and engagement remains unchanged (emphasis added):

“Union democracy is not just right in principle. It is the best way to maximise members’ unity in action and the only way to win. Members have a right to decide what action they take and what kind of deal will end the dispute. These decisions must be taken as a result of proper debate, not on the basis of survey questions written at Head Office.”

This reflects the vanguardist approach of the SWP: claiming to be for greater democracy while opposing attempts, by central office or branch committees, to engage with less active members, who are expected to follow unquestioningly the activist vanguard.

The example provided by the University of Manchester branch, UCU’s second largest with over 2000 members, provides further insights. For years the branch was almost faction free and made increasing use of e-surveys to consult, inform and mobilise members while successfully fighting off hundreds of compulsory redundancies in 2015 and 2017 and playing a leading role in the 2018 USS dispute. For example, in March 2018 over 800 members responded to a pre-BDM e-survey (held after a meeting attended by around 200) asking their views about UUK’s offer to set up the USS Joint Expert Panel in return for a suspension of further USS strikes.

However, in 2019, an SWP member, David Swanson, became branch president, the UCU Left website boasted that the branch had been taken over from the “right-wing” IBL faction, and use of e-surveys more or less ended. Instead, in January 2020, after he and his supporters had rejected another e-consultation on the basis that complicated issues must be debated in person and could not be reduced to binary questions, Swanson reported that 85-90% of members had voted for 14 more days of strikes and making resolution of the USS and ‘Four Fights’ disputes dependent on each other – all on the basis of three 20 minute meetings attended by a total of 40 members, less than 2% of the branch. The latest pre-BDM branch meeting this January was better attended (130 equal to 7% of the branch) but again there was no e-survey of the wider membership.

(In)Effectiveness of recent strikes

In 2019-20 and again in 2021-22, UCU Left delegates argued for further rounds of sustained collective action, and the union took a grand total of 50 days strike action in the USS and ‘Four Fights’ disputes before they petered out in summer 2022. The strikes achieved almost nothing and, more worryingly, revealed clear evidence of union weakness. The number of branches with strike turnouts above 50 per cent declined steadily between 2018 and April 2022; over 40 per cent of members regularly abstained from the ballots; and strike action was heavily concentrated in the ‘old’ universities with involvement from less than 20 per cent of new universities.

The UCU Left policy of ‘sustained strike action’ had clearly failed to move the employers and clearly failed to mobilize large swathes of union membership. Yet UCU Left leaders were undeterred by these problems because of their ideological commitment to the strike as a weapon of class struggle and class consciousness raising. Consequently, the UCU Left members on HEC, who together with a few other independent members hold a controlling majority, voted in November 2022 for indefinite strike action, without any reflection on why ‘sustained strike action’ had failed and without any analysis of likely membership support for the new policy since there had been no consultation with members or branches about indefinite strikes. Their incuriosity about membership attitudes is arguably a reflection of their crude model of leadership: if the militant minority can pass branch and conference motions in favour of strike action, then the majority of members will follow union policy. The reality is that members need to be persuaded and many members think for themselves, about strike outcomes and costs and about the balance of power. Effective leadership involves continual dialogue between different groups in an organization in order to build consensus, not edicts from revolutionary minorities at poorly attended meetings.

Conclusion and NEC elections

In short, UCU Left is an organization built and controlled by Trotskyist militants who are contemptuous of collective bargaining and collective agreements. They are keen to exploit poorly attended meetings and to work with militant minorities in order to promote strike action wherever possible. Strike action may achieve substantive gains in terms and conditions but for the Trotskyist core of UCU Left, the principal benefits of strike action are to be found in the development of class consciousness and the building of the revolutionary party, the SWP. Their primary loyalty is always to the party, not to UCU, and union members may want to consider this fact when voting in the NEC elections.

Footnotes:

[1] Information from UCU Left website, https://uculeft.org/, accessed 13 January 2023.

[2] In an interview with John Kelly around six years ago, SWP member Jane Hardy confirmed that UCU Left’s 15-person executive committee normally included 11-12 SWP members; and pre-Covid, three SWP leaders of UCU Left on NEC, Sean Wallis, Sean Vernell, and Carlo Morelli, were observed meeting with the SWP industrial organiser, Mike Bradley, in a café nearby UCU’s Carlow Street offices before they went to the UCU Left caucus meeting in another café before NEC meetings.

[3] See ‘What We Stand For’ in any issue of Socialist Worker.

[4] Final quote from Socialist Worker 11 January 2023, p.7; others from J. Choonara and C. Kimber, Arguments for Revolution: the case for the Socialist Workers Party, Bookmarks, 2011, pp. 42, 47, 81 and 82.

[5] A. Callinicos, The Revolutionary Road to Socialism: What the Socialist Workers Party Stands For, Bookmarks, 1983, p. 35.

[6] SWP Pre-Conference bulletin 2 (2007) Pay, Brown and the fight in the Unions, Statement from Central Committee p,5.

[7] See ‘What We Stand For’ in any issue of Socialist Worker.

[8] T. Cliff, The Crisis: Social Contract or Socialism, Pluto Press, 1975, p. 182.